Gabriela Ravete Cavalcante1, Marcela Cangussu Barbalho-Moulim1, Veronica Lourenço Wittmer1, Halina Duarte1, Daniella Cristina De Assis Pinto Gomes1, Michelly Louise Sartório Altoé Toledo2, Alexandre Bittencourt Pedreira2, Flávia Marini Paro1

1Departamento de Educação Integrada em Saúde, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (UFES), Vitória, ES, Brasil

2Hospital Universitário Cassiano Antônio Moraes (HUCAM), Empresa Brasileira de Serviços Hospitalares (EBSERH), Vitória, ES, Brasil

Received: March 5, 2025; Accepted: May 12, 2025.

Correspondence: Flávia Marini Paro, flamarp@yahoo.com

Como citar

Cavalcante GR, Barbalho-Moulim MC, Wittmer VL, Duarte H, Gomes DCAP, Toledo MLSA, Pedreira AB, Paro FM. Effects of an intradialytic protocol involving electrical stimulation of the upper limb associated with a cycle ergometer in the lower limb on the quality of life of individuals with chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Fisioter Bras. 2025;26(3):2170-2190. doi:10.62827/fb.v26i3.1060

Abstract

Introduction: Intradialytic exercises have several benefits for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD); however, no studies have used neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) in the upper limbs (UL) during these exercises to assess quality of life (QoL). Objective: To evaluate the effects of unilateral NMES in the UL superimposed on a voluntary contraction associated with an intradialytic exercise protocol with a lower limb cycle ergometer on the QoL of adults with CKD. Methods: This randomized, controlled clinical trial was conducted on adult patients diagnosed with CKD who were undergoing hemodialysis (HD) at a university hospital. The protocol included aerobic exercises with a lower limb cycle ergometer and NMES in UL in the intervention group (IG) and a lower limb cycle ergometer and NMES sham in UL in the control group (CG) for 8 weeks. QoL was assessed via the Kidney Disease and Quality-of-Life Short Form (KDQOL-SFTM) questionnaire. Results: This study included 9 participants who presented low self-reported QoL, with low scores in the physical component (37.78 ± 10.42) and mental component (41.96 ± 14.88) of the KDQOL-SFTM. Furthermore, the intervention did not cause any change in these scores. Conclusion: Patients with CKD on HD have low self-reported QoL, with low scores on the physical and mental components of the KDQOL-SFTM. Unilateral NMES in the UL superimposed on a voluntary contraction associated with a cycle ergometer on the lower limb had no effect on the physical or mental components of quality of life.

Keywords: Kidney Failure; Electrical Stimulation; Exercise; Quality of Life.

Resumo

Introdução: Os exercícios intradialíticos apresentam diversos benefícios para pacientes com doença renal crônica (DRC); entretanto, nenhum estudo utilizou a estimulação elétrica neuromuscular (EENM) nos membros superiores (MS) durante esses exercícios para avaliar a qualidade de vida (QV). Objetivo: Avaliar os efeitos da EENM unilateral no MMSS simultânea a uma contração voluntária, associada a um protocolo de exercício intradialítico com cicloergômetro de membros inferiores na qualidade de vida de adultos com DRC. Métodos: Este ensaio clínico randomizado e controlado foi conduzido em pacientes adultos com diagnóstico de DRC em hemodiálise (HD) em um hospital universitário. O protocolo incluiu exercícios aeróbicos com cicloergômetro de membros inferiores e EENM em MMSS no grupo intervenção (GI), e cicloergômetro de membros inferiores e simulação de EENM em MMSS no grupo controle (GC) por 8 semanas. A qualidade de vida foi avaliada por meio do questionário Kidney Disease and Quality-of-Life Short Form (KDQOL-SFTM). Resultados: Este estudo incluiu 9 participantes que apresentaram baixa qualidade de vida autorrelatada, com baixas pontuações nos componentes físico (37,78 ± 10,42) e mental (41,96 ± 14,88) do KDQOL-SFTM. Além disso, a intervenção não causou nenhuma alteração nessas pontuações. Conclusão: Pacientes com DRC em HD apresentam baixa qualidade de vida autorrelatada, com baixas pontuações nos componentes físico e mental do KDQOL-SFTM. A EENM unilateral no membro superior sobreposta a uma contração voluntária associada a um cicloergômetro no membro inferior não teve efeito nos componentes físico ou mental da qualidade de vida.

Palavras-chave: Insuficiência Renal; Estimulação Elétrica; Exercício; Qualidade de Vida.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been one of the main causes of mortality and morbidity in the 21st century [1], and hemodialysis (HD) is the most commonly used kidney replacement therapy [2].

CKD causes changes in patients’ daily lives and a significant reduction in their quality of life (QoL) [3], and a worse QoL has been significantly associated with increased mortality in patients with CKD [4, 5].

CKD patients are approximately 35% less active than healthy sedentary people are [6] and have a high prevalence of poor cardiorespiratory fitness [7]. This directly influences QoL, as the literature shows an association between lower levels of physical activity and the worsening of this variable [8]. On the other hand, it is already well established in the literature that improving QoL is one of the benefits of physical exercise for these patients [9-11]. According to a systematic review, intradialytic exercises performed at least three times a week, with an average of 30 minutes per session, for 8 weeks improve patients’ physical function, depression, and QoL [12].

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) can be an alternative to intradialytic exercise, as these individuals have low tolerance to overload, which often makes conventional training unfeasible [13]. The use of NMES in lower limbs during HD is safe, effective [14-15] and offers minimal risks at low operational costs [16]. Its use in the lower limbs has been shown to have beneficial effects, such as increased muscle strength [13-15, 17], functional capacity [15,17], protection against muscular atrophy [13] and improved QoL [14, 18-19]. However, no studies have used the NMES in the upper limbs (UL) during intradialytic exercises to assess QoL.

A survey carried out with people who performed HD for more than one month revealed manual dysfunctions in 54% of the participants, leading to significant impairments in activities of daily living [20]. Furthermore, these individuals are at greater risk of deficits in the long head of the biceps and a marked reduction in muscle strength than people of the same age and sex without CKD. Such changes occur mainly in UL with the fistula or graft and are related to greater limitations [18]. Therefore, adequate exercise programs must be implemented to maintain UL mobility and strength [18].

Unilateral NMES constitutes a proposal for performing intradialytic exercises in UL without risks for the fistula, as it has been demonstrated that resistance exercises in just one limb lead to strength gains in the contralateral limb as well [21-22].

Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of unilateral NMES in UL superimposed on a voluntary contraction associated with an intradialytic exercise protocol with a lower limb cycle ergometer on the physical and mental composites of the QoL of adults with CKD.

Methods

Study design

This randomized controlled clinical trial followed the Consolidated Reporting Standards (CONSORT) guidelines and their guide for nonpharmacological interventions.

The study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Cassiano Antônio Moraes (HUCAM), Vitória (ES), Brazil (CAAE 27067819.1.0000.5071 and approval n° 5.614.016). The project was registered on the platform: https://clinicaltrials.gov/, under number NCT05374863, and the research protocol was previously published [23].

Participants and eligibility

Participants were recruited from the HUCAM HD Center. Individuals who met the following inclusion criteria were included in the study: having a diagnosis of CKD; being in HD on HUCAM for at least 3 months; presenting a hemoglobin level > 9 g/dL; presenting clinical stability for at least 3 months; not being part of another physical exercise program; being able to carry out assessment tests; being 18 years of age or older; and agreeing to participate in the research by signing the Informed Consent (IC).

Individuals who presented symptoms or health conditions (cardiovascular, respiratory, orthopedic, neurological, or cognitive) that limited their ability to participate in the assessment tests and exercise program, as well as conditions considered contraindications for NMES, such as infections, skin rashes or hyperesthesia in the region where NMES would be applied, were excluded.

Randomization

The allocation was blind, and the participants were distributed into two groups, the intervention group (IG) and the control group (CG), through a computer-generated list via a simple balanced randomization method (1:1).

The IG underwent unilateral NMES reaching the motor threshold in the UL without HD fistula for 20 min, and the CG underwent unilateral NMES-sham reaching only the sensory threshold in the UL without HD fistula for 20 min. In addition, both groups exercised using a leg cycle ergometer for 30 min.

The outcome data was collected by trained researchers who were blinded to the participant group allocation.

An intention-to-treat analysis was used to reduce the risk of bias, and the statistical analysis was carried out by researchers blinded to participant group allocation.

Procedures

The treatment was carried out for 8 weeks, with three weekly sessions totaling 24 sessions.

In daily pre- and postintervention assessments, the following items were checked and recorded to ensure participants’ safety: weight; blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), dyspnea and fatigue in the lower limbs assessed by the Modified Borg Scale (Borg CR10), from zero to 10 [24]; and pain assessed by the visual analog scale (VAS), HD duration, NMES intensity parameters, symptoms, and complications or adverse events.

The criteria for starting exercise were as follows: glomerular ultrafiltration rate < 13 mL/min/1.73 m2; BP < 180/100 or >100/50 mmHg; resting HR < 100 bpm; no hospitalization or illness in the last week; no abnormal symptoms (cold, flu, headache, dizziness, nausea, etc.); controlled blood sugar levels (between 7 and 14 mmol or 126 and 252 mg dL−1); and resting SpO2 above 90% [25].

In the first 2 hours of each HD session, participants performed leg cycle ergometer exercises and unilateral or sham NMES in the UL. Each intervention lasted 70 minutes and was distributed as follows: 10 minutes for initial assessment; 30 minutes of aerobic cycle ergometer exercise; 20 minutes of active or sham NMES; and 10 minutes for final evaluation.

The criteria for discontinuing exercise were SpO2 < 88% [26]; BP > 180/105 mmHg [27]; chest pain; dyspnea; palpitations; bronchospasm; exercise intolerance; confusion; dizziness; and pallor and/or cyanosis [23]. In this case, the program was only allowed to continue after complete remission of symptoms, reassessment, and authorization by the multidisciplinary team.

Aerobic exercise with a cycle ergometer

Aerobic exercise was performed on a cycle ergometer (Mini Bike E5 Acte Sports®) positioned in front of the HD chair and consisted of three phases: warm-up (5 minutes), conditioning (20 minutes), and cool-down (5 minutes). During the warm-up and cool-down phases, patients were instructed to maintain a lower exercise intensity, between 1 and 3 on the Borg CR10 scale. During the conditioning phase, patients were instructed to increase exercise intensity, reaching levels between 4 and 7 on the Borg CR10 scale. Patients were questioned every 5 minutes about their exertion level, and the cycle ergometer load was adjusted to reach an intensity between 4 and 7 on the Borg CR10 scale.

EENM

NMES was performed for 20 minutes, using specific equipment (Neurodyn II Ibramed®), with the patient sitting in the HD chair.

The UL muscles without the fistula were stimulated unilaterally with four electrodes (5 × 5 cm for the biceps and 5 × 3 cm for the finger flexors) placed on the limb via the myoenergetic technique, with 2 positioned longitudinally on the muscle belly of the biceps and two others in the ventral region of the forearm. The UL was positioned at the side of the body with slight flexion of the elbow and the forearm in supination. The muscles were stimulated according to the following parameters: frequency of 80 Hz, pulse width of 350 µs, on time of 5 s, and off time of 10 s. The intensity was adjusted individually and progressively for each patient to achieve the greatest degree of pain-free contraction. For the sham NMES, the electrodes were similarly positioned on the UL; however, the current intensity only reached the sensory threshold.

The IG was instructed to perform isometric contraction of the wrist and finger flexors during NMES (squeezing a ball) because there is evidence that NMES superimposed on a voluntary contraction can cause increased muscle activation with less discomfort than can NMES alone [28].

Study outcomes

QoL assessments were carried out at two stages of the study: before the start of treatment (week 0) and at its end (week 9), always during the second HD session of the week. The outcomes evaluated are described below.

QoL was assessed via the Kidney Disease and Quality-of-Life Short Form questionnaire (KDQOL-SFTM) [29], which is a specific instrument for assessing QoL in patients with CKD and applies to patients undergoing HD. It is a self-administered questionnaire with 80 items divided into 19 scales, which take approximately 16 minutes to answer. It includes generic and specific aspects related to kidney disease [29].

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed via the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0 software. For descriptive analysis, continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQ), and categorical variables are presented as absolute (n) and relative frequencies (%). The Shapiro‒Wilk test was used to evaluate the normality of the data. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare the pre- and postintervention moments of the mental and physical composites. The delta value was calculated by subtracting the pre-intervention quality of life scores from the post-intervention quality of life scores in each group to estimate the effect of the intervention in each group. After that the Wilcoxon test was used to compare the deltas of control and intervention groups, with p ≤ 0.05 considered significant.

Results

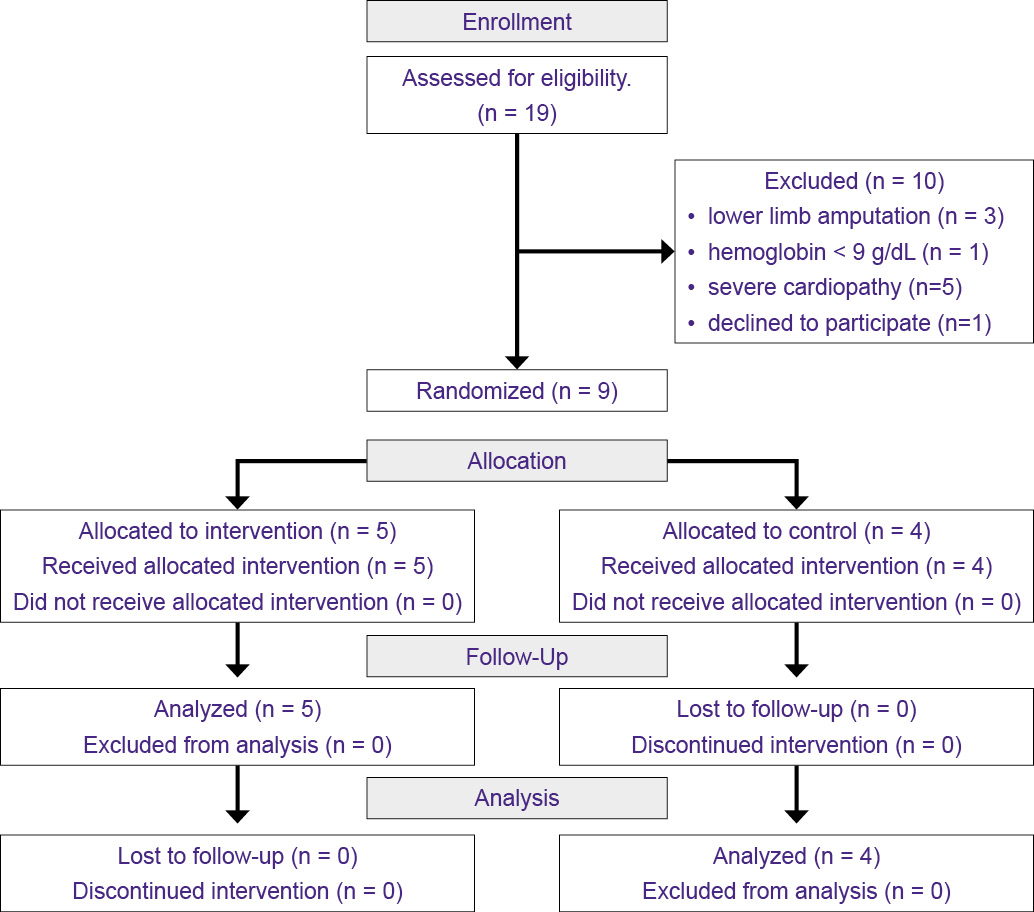

The sample consisted of 9 participants, who were randomly allocated to the CG (n = 4) or the IG (n = 5), as shown in the flowchart (Figure 1), which also shows the number of eligible, excluded, and included participants in the study.

Figure 1 - Participant recruitment and follow-up flowchart - CONSORT

Table 1 shows the participants’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, which were similar between the groups. The IG was composed mainly of males (60%), with a mean age of 40 ± 13 years, dry weight of 64.6 ± 4.8 kg, BMI of 22.9 ± 2.1, HD time of 78 ± 49 months, and hypertension as the most common comorbidity (60%). In the CG, male sex (75%) was also the most prevalent sex, the average age was 38 ± 16 years, the dry weight was 70.5 ± 13.1, the BMI was 26.5 ± 5.6, the HD time was 56 ± 29 months, and hypertension was also the most prevalent comorbidity (100%).

Table 1 - Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants

|

CG (n= 4) |

IG (n= 5) |

|

|

Sex, n (%) |

||

|

Female |

1 (11.1%) |

2 (22.2%) |

|

Male |

3 (33.3%) |

3 (33.3%) |

|

Age (years), mean ± SD |

40 ± 13 |

38 ± 16 |

|

Height (meter), mean ± SD |

1.68 ± 0.05 |

1.63 ± 0.07 |

|

Dry weight (kg), mean ± SD |

64.6 ± 4.81 |

70.5 ± 13.1 |

|

BMI, mean ± DP |

22.9 ± 2.12 |

26.5 ± 5.6 |

|

Skyn color, n (%) |

||

|

Black |

2 (22.2%) |

1 (11.1%) |

|

Brown |

1 (11.1%) |

2 (22.2%) |

|

White |

1 (11.1%) |

2 (22.2%) |

|

Time on HD (m), mean ± SD |

78 ± 49 |

56 ± 29 |

|

Hypertension, n (%) |

4 (44.4%) |

3 (33.3%) |

|

Diabetes, n (%) |

1 (11.1%) |

1 (11.1%) |

|

Chronic pulmonary disease, n (%) |

1 (11.1%) |

0 |

|

Cardiopathy, n (%) |

0 |

2 (22.2%) |

|

Dyslipidemia, n (%) |

1 (11.1%) |

0 |

|

Hepatitis, n (%) |

1 (11.1%) |

0 |

|

Orthopedic disease, n (%) |

1 (11.1%) |

2 (22.2%) |

CG: control group; IG: intervention group; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; HD, hemodialysis.

Table 2 shows the scores obtained in the physical and mental composites and in other domains of the KDQOL-SF™ questionnaire by participants in each group in the pre- and postintervention periods and the comparisons between these periods. At the preintervention time point, the IG score was lower for the physical composite (45.4 ± 8.71) than for the mental composite (52.5 ± 9.32), which remained after the intervention. The CG also had a lower score in the physical composite (37.78 ± 10.42) than in the mental composite (41.96 ± 14.88) at the pre- and postintervention time points.

Table 2 - KDQOL-SF™ domain scores pre- and post-intervention for IG and CG.

|

CG |

IG |

|||||||

|

Pre-intervention (n=4) |

Post-intervention (n=4) |

Pre-intervention (n=5) |

Post-intervention (n=5) |

|||||

|

Variables |

Mean ± SD |

Median (IQ) |

Mean ± SD |

Median (IQ) |

Mean ± SD |

Median (IQ) |

Mean ± SD |

Median (IQ) |

|

Symptom/ problem list |

81.54 ± 10.03 |

85.4 (20.4) |

81.8 ± 11.7 |

83.3 (23.9) |

81.7 ± 9.92 |

79.2 (16.7) |

66.1 ± 29.2 |

68.2 (60.42) |

|

Effects of kidney disease |

41.41 ± 12.34 |

37.5 (17.2) |

53.9 ± 18.9 |

48.4 (28.1) |

46.9 ± 22.86 |

37.5 (6.3) |

56.3 ± 30.3 |

59.4 (43.8) |

|

Burden of kidney disease |

32.81 ± 17.95 |

40.6 (37.5) |

40.6 ± 10.8 |

43.7 (21.9) |

45.0 ± 27.74 |

31.3 (56.3) |

45.0 ± 40.4 |

25.0 (68.8) |

|

Work status |

12.5 ± 25.0 |

0 (25) |

62.5 ± 47.9 |

75.0 (100) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Cognitive function |

83.33 ± 15.87 |

83.3 (30) |

78.3 ± 11.4 |

76.7 (20) |

78.7 ± 15.2 |

73.3 (26.7) |

88.0 ± 16.6 |

100.0 (33.3) |

|

Quality of social interaction |

65.0 ± 19.15 |

70.0 (40) |

83.3 ± 8.6 |

83.3 (16.7) |

80.0 ± 12.47 |

80.0 (13.3) |

60.0 ± 9.4 |

66.7 (20) |

|

Sexual function |

93.75 ± 12.5 |

100.0 (25) |

91.7 ± 14.4 |

100.0 (25) |

84.4 ± 31.25 |

100.0 (62.5) |

93.8 ± 12.5 |

100.0 (25) |

|

Sleep |

63.13 ± 5.54 |

62.5 (10) |

70.0 ± 9.1 |

70.0 (17.5) |

76.5 ± 13.3 |

75.0 (27.5) |

70.5 ± 22.7 |

57.5 (37.5) |

|

Social support |

45.83 ± 41.67 |

41.7 (75) |

83.3 ± 33.3 |

100.0 (66.7) |

90.0 ± 9.13 |

83.3 (16.7) |

50.0 ± 40.8 |

66.7 (66.7) |

|

Dialysis staff encouragement |

100.00 ± 0 |

100.00 (0) |

96.9 ± 6.25 |

100.0 (12.5) |

82.5 ± 16.77 |

75.0 (37.5) |

80.0 ± 16.8 |

87.5 (25) |

|

Overall Health |

67.50 ± 23.63 |

60.00 (35) |

77.5 ± 18.9 |

85.0 (40) |

67.5 ± 20.62 |

65.0 (35) |

70.0 ± 39.4 |

90.0 (90) |

|

Patient satisfaction |

91.67 ± 16.67 |

100.00(33.3) |

87.5 ± 25.0 |

100.0 (50) |

70.0 ± 18.26 |

66.7 (16.67) |

50.0 ± 37.3 |

50.0 (66.7) |

|

Physical functioning |

68 ± 18 |

65 (33) |

73.8 ± 23.2 |

77.5 (47.5) |

83 ± 19 |

90 (40) |

72.0 ± 42.07 |

90.0 (100) |

|

Role--physical |

6 ± 13 |

0 (13) |

25.0 ± 50.0 |

0 (50) |

70 ± 41 |

100 (75) |

70.0 ± 44.7 |

100.0 (100) |

|

Pain |

44.38 ± 37.66 |

28.8 (47.5) |

55.6 ± 33.1 |

55.0 (61.3) |

72.0 ± 32.76 |

80.0 (77.5) |

69.0 ± 30.9 |

67.5 (67.5) |

|

General health |

44 ± 19 |

45 (35) |

40 ± 23 |

38 (40) |

55 ± 26 |

65 (45) |

62 ± 28 |

70 (65) |

|

Emotional well-being |

63 ± 21 |

72 (42) |

80 ± 15 |

82 (30) |

77 ± 12 |

72 (24) |

65 ± 25 |

64 (44) |

|

Role-emotional |

8.33 ± 16.67 |

0 (16.7) |

58.3 ± 50.0 |

66.7 (100) |

80.0 ± 44.72 |

100.0 (100) |

60.0 ± 54.8 |

100.0 (100) |

|

Social function |

59.38 ± 25.77 |

56.3 (43.8) |

71.9 ± 32.9 |

81.3 (68.8) |

77.5 ± 22.36 |

75.0 (50) |

62.5 ± 25.0 |

50.0 (37) |

|

Energy/fatigue |

46 ± 21 |

43 (35) |

66 ± 27 |

68 (53) |

68 ± 13 |

70 (30) |

73 ± 18 |

75 (30) |

|

Physical Composite |

37.78 ± 10.42 |

36.7 (18.7) |

39.0 ± 13.05 |

39.7 (24.1) |

45.4 ± 8.71 |

42.3 (15.6) |

47.06 ± 6.8 |

43.8 (13.3) |

|

Mental Composite |

41.96 ± 14.88 |

43.8 (29.8) |

51.9 ± 5.26 |

50.8 (8,7) |

52,5 ± 9,32 |

57,3 (21,2) |

45,9 ± 12,4 |

46,4 (23,6) |

CG: control group; IG: intervention group; SD, standard deviation; IQ, interquartile interval.

The scores for physical and mental composites did not significantly differ between the pre- and postintervention timepoints in either group when the Wilcoxon test was used. In the CG, the physical composite changed from a median (IQ) of 36.7 (18.7) to 39.7 (24.1), p = 1,0, and the mental composite changed from 43.8 (29.8) to 50.8 (8,7), p = 0,14. In the IG, the physical composite changed from 42.3 (15.6) to 43.8 (13.3), p = 0,22, and the mental composite changed from 57,3 (21,2) to 46,4 (23,6), p = 0,08 (p-values not included in the table).

No significant differences were detected between the groups (Table 3).

Table 3 - Comparison of the deltas of the intervention effects between the control and intervention groups

|

Variables |

CG |

IG |

p-value |

|

Symptom/ problem list |

0.00 |

0.49 |

0.46 |

|

Effects of kidney disease |

0.46 |

0.32 |

1.00 |

|

Burden of kidney disease |

0.22 |

0.16 |

0.85 |

|

Work status |

0.81 |

0 |

0.10 |

|

Cognitive function |

0.50 |

0.47 |

0.14 |

|

Quality of social interaction |

0.64 |

0.91 |

0.14 |

|

Sexual function |

0.00 |

0.44 |

0.65 |

|

Sleep |

0.46 |

0.3 |

0.45 |

|

Social support |

0.53 |

0.82 |

0.14 |

|

Dialysis staff encouragement |

0.50 |

0.16 |

0.59 |

|

Overall Health |

0.40 |

0.2 |

1.00 |

|

Patient satisfaction |

0.50 |

0.6 |

0.18 |

|

Physical functioning |

0.53 |

0.2 |

0.70 |

|

Role--physical |

0.22 |

0 |

1.00 |

|

Pain |

0.09 |

0.16 |

1.00 |

|

General health |

0.27 |

0.43 |

0.19 |

|

Emotional well-being |

0.36 |

0.67 |

0.14 |

|

Role-emotional |

0.70 |

0.44 |

0.41 |

|

Social function |

0.40 |

0.57 |

0.65 |

|

Energy/fatigue |

0.73 |

0.43 |

1.00 |

|

SF-12 Physical Composite |

0.00 |

0.54 |

0.27 |

|

SF-12 Mental Composite |

0.73 |

0.78 |

0.46 |

CG: control group; IG: intervention group. Wilcoxon test.

Discussion

The results of the present study indicate that patients with CKD undergoing HD have low self-reported QoL, reaching low scores mainly in the physical composite of the KDQOL-SFTM in both groups. There were no significant effects of the intervention between the pre- and postintervention assessments in any group. There were also no differences observed between the groups in the deltas at the pre- and post-intervention time points.

The lower scores observed in the physical composite corroborate the evidence showing that although these individuals have low scores in the physical and mental composites, they have a worse perception of QoL related to the physical composite [4,10,30]. A recent systematic review indicated that disease symptoms limit physical activity and interfere with daily activities and regular work, causing patients’ poor perception of their health status and compromising their well-being due to their physical state [31]. Notably, the impairment of this composite has been strongly associated with a high mortality rate and a high rate of hospitalization in these patients [32].

Although this study did not find positive effects of the selected intervention on the physical composite, there are systematic reviews reporting that intradialytic exercises significantly improve this composite [10,12,33-34]. The small sample size of the present study may have influenced this result, as a trend of increasing was observed, although it was not significant.

With respect to the mental composite, most systematic reviews corroborate what was found in this study, finding no significant improvements in this variable [10,12,34], except for a single one that shows some positive effect on the mental composite [33]. Adults with CKD who use HDs and who are undergoing exercise protocols have improved QoL, with increased scores in different domains, especially in the physical function domain [35]. In addition, intradialytic exercise provides other benefits, such as improved aerobic capacity, BP, and muscle strength [36], which may reflect the perception of the physical composite of the KDQOL-SFTM.

The IG obtained the worst scores in the domains ‘work status’, ‘burden of kidney disease’, and ‘effects of kidney disease’, which have also been reported as being some of the worst scores in other studies [4,31-32,37]. Furthermore, the ‘work status’ domain, which achieved the lowest score in both groups, was also frequently associated with worse QoL by other authors [31-32,37]. One hypothesis for this finding is that most participants did not have a job due to the obligation to go to HD 3x/week, combined with their health condition, which makes it difficult for them to be professionally active. Additionally, there is evidence that unemployed patients are more likely to have a worse QoL than those who are professionally active [38].

The ‘dialysis staff encouragement’ domain had among the highest scores in both the IG and the CG, corroborating the findings of other studies [31-32,37]. In a study on participants’ perceptions regarding the installation of intradialytic exercises, patients reported that the dialysis team and the interventionist were their main sources of support, indicating that this encouraged them to participate in the protocol through word incentives [39]. The encouragement of the dialysis team is an important factor in patients’ adherence to the protocols, as they become a support network, encouraging them to participate and being a key element in implementation.

The main limitation of this study is related to the small sample size, which makes the results difficult to replicate for the general population and increases the risk of statistical inaccuracies, but it is a pilot study that will be replicated in other HD shifts from the hospital. The main strength of this study is that it is the first to use UL-NMES associated with a leg cycle ergometer in an intradialytic protocol, which may contribute to the development of other similar intradialytic protocols. Other strengths included randomization, secret allocation and intention-to-treat analysis.

Conclusion

Unilateral NMES in the UL superimposed on a voluntary contraction associated with a leg cycle ergometer had no effect on the physical and mental composites of QoL. However, the results of this study must be analyzed with caution considering the small sample size and because it is a pilot study. Therefore, the need for more studies with larger sample sizes is highlighted to elucidate the benefits of NMES in UL on the QoL of adult patients with CKD undergoing HD.

Ethical Approval

The study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Cassiano Antônio Moraes (HUCAM), Vitória (ES), Brazil (CAAE 27067819.1.0000.5071 and approval n° 5.614.016).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Cassiano Antônio de Moraes University Hospital (HUCAM) and the Brazilian Hospital Services Company (EBSERH) for allowing the research to be carried out at the Hemodialysis Center.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Financial support

The researcher Gabriela Ravete Cavalcante received a scholarship from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq; funding code 001) while participating in this project = Commitment term of the UFES Scientific Initiation Program signed on September 1, 2023, without number.

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design of the research: Cavalcante GR, Barbalho-Moulim MC, Paro FM, Wittmer VL, Duarte H, Pedreira AB; Data collection: Cavalcante GR, Barbalho-Moulim MC, Gomes DCAP, Toledo MLSA; Data analysis and interpretation: Cavalcante GR, Paro FM, Barbalho-Moulim MC; Manuscript writing: Cavalcante GR, Barbalho-Moulim MC, Paro FM; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Cavalcante GR, Barbalho-Moulim MC, Paro FM, Wittmer VL, Duarte H, Pedreira AB, Gomes DCAP, Toledo MLSA.

References

1. Kovesdy CP. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl. 2022;12(1):7-11. Available from: https://www.kisupplements.org/article/S2157-1716(21)00066-6/fulltext .doi:10.1016/j.kisu.2021.11.003

2. Bello AK, Levin A, Lunney M, Osman MA, Ye F, Ashuntantang GE et al. Status of care for end stage kidney disease in countries and regions worldwide: international cross sectional survey. BMJ. 2019;367: l5873. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/367/bmj.l5873. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5873

3. Rebollo-Rubio A, Morales-Asencio JM, Pons-Raventos ME, Mansilla-Francisco JJ. Revisión de estudios sobre calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en la enfermedad renal crónica avanzada en España. Nefrol Madr. 2015;35(1):92–109. Available from: https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/nefrologia/v35n1/revision.pdfdoi:10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2014.Jul.12133

4. Gebrie MH, Asfaw HM, Bilchut WH, Lindgren H, Wettergren L. Health-related quality of life among patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2023;21:36. Available from: https://hqlo.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12955-023-02117-x. doi:10.1186/s12955-023-02117-x

5. Haraldstad K, Wahl A, Andenæs R, Andersen JR, Andersen MH, Beisland E, et al. A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:2641-2650. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11136-019-02214-9. doi:10.1007/s11136-019-02214-9

6. Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Ng AV, Carey S, Schoenfeld PY, Kent-Braun JA, et al. Physical activity levels in patients on hemodialysis and healthy sedentary controls. Kidney Int. 2000;57:2564–2570. Available from: https://www.kidney-international.org/article/S0085-2538(15)47016-4/fulltext. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00116.x.

7. Andrade FP, Borba CF, Ribeiro HS, Rovedder PME. Cardiorespiratory fitness and mortality risk in patients receiving hemodialysis: a prospective cohort. Braz J Nephrol. 2024;46:39-46. Available from: https://www.bjnephrology.org/en/article/cardiorespiratory-fitness-and-mortality-risk-in-patients-receiving-hemodialysis-a-prospective-cohort/ doi:10.1590/2175-8239-JBN-2022-0124pt

8. López MTM, Rodríguez-Rey R, Montesinos F, Galvins SR, Ágreda-Ladrón MR, Mayo EH. Factors associated with quality of life and its prediction in kidney patients on haemodialysis. Nefrologia. 2022;42(3):318-326. Available from: https://www.revistanefrologia.com/es-linkresolver-factors-associated-with-quality-life-S2013251422000852 . doi:10.1016/j.nefroe.2022.07.007

9. Gomes Neto M, de Lacerda FFR, Lopes AA, Martinez BP, Saquetto MB. Intradialytic exercise training modalities on physical functioning and health-related quality of life in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil.2018;32(9):1189-1202. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0269215518760380?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed. Doi:10.1177/0269215518760380

10. Hu H, Liu X, Chau PH, Choi EPH. Effects of intradialytic exercise on health-related quality of life in patients undergoing maintenance haemodialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Life Res. 2022; 31(7):1915–1932. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11136-021-03025-7. doi:10.1007/s11136-021-03025-7

11. Moeinzadeh F, Shahidi S, Shahzeidi S. Evaluating the effect of intradialytic cycling exercise on quality of life and recovery time in hemodialysis patients: A randomized clinical trial. J Res Med Sci. 2022;27:84. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jrms/fulltext/2022/27000/evaluating_the_effect_of_intradialytic_cycling.84.aspx. doi:10.4103/jrms.jrms_866_21

12. Chung Y-C, Yeh M-L, Liu Y-M. Effects of intradialytic exercise on the physical function, depression and quality of life for haemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(13-14):1801–1813. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jocn.13514. doi:10.1111/jocn.13514

13. Schardong J, Dipp T, Bozzeto CB, da Silva MG, Baldissera GL, Ribeiro RDC, et al. Effects of Intradialytic Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation on Strength and Muscle Architecture in Patients With Chronic Kidney Failure: Randomized Clinical Trial. Artif Organs. 2017;41:1049-1058. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/aor.12886. doi:10.1111/aor.12886

14. Simó VE, Jiménez AJ, Oliveira JC, Guzmán FM, Nicolás MF, Potau MP, Solé AS, et al. Efficacy of neuromuscular electrostimulation intervention to improve physical function in haemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47(10):1709-1717. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11255-015-1072-3. doi:10.1007/s11255-015-1072-3

15. Valenzuela PL, Morales JS, Ruilope LM, de la Villa P, Santos-Lozano A, Lucia A. Intradialytic neuromuscular electrical stimulation improves functional capacity and muscle strength in people receiving haemodialysis: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2020;66(2):89-96. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1836955320300230?via%3Dihub. doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2020.03.006

16. Jones S, Man WD-C, Gao W, Higginson IJ, Wilcock A, Maddocks M. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for muscle weakness in adults with advanced disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10(10):CD009419. Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009419.pub3/full. Doi:10.1002/14651858.

17. Esteve V, Carneiro J, Moreno F, Fulquet M, Garriga S, Pou M, et al. The effect of neuromuscular electrical stimulation on muscle strength, functional capacity and body composition in haemodialysis patients. Nefrologia. 2017;37(1):68-77. Available from: https://www.revistanefrologia.com/es-linkresolver-efecto-electroestimulacion-neuromuscular-sobre-fuerza-S0211699516300741. doi:10.1016/j.nefro.2016.05.010

18. Capitanini A, Galligani C, Lange S, Cupisti A. Upper limb disability in hemodialysis patients: evaluation of contributing factors aside from amyloidosis. Ther Apher Dial. 2012;16:242–247. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-9987.2011.01056.x. doi:10.1111/j.1744-9987.2011.01056.x

19. Dobsak P, Homolka P, Svojanovsky J, Reichertova A, Soucek M, Novakova M, et al. Intra-dialytic electrostimulation of leg extensors may improve exercise tolerance and quality of life in hemodialyzed patients. Artif Organs. 2012;36(1):71-78. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1525-1594.2011.01302.x . doi:10.1111/j.1525-1594.2011.01302.x

20. Kutsuna T, Matsunaga A, Takagi Y, Motohashi S, Yamamoto K, Matsumoto T, et al. Development of a novel questionnaire evaluating disability in activities of daily living in the upper extremities of patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Ther Apher Dial. 2011;15(2):185-194. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-9987.2010.00905.x. doi:10.1111/j.1744-9987.2010.00905.x

21. Manca A, Dragone D, Dvir Z, Deriu F. Cross-education of muscular strength following unilateral resistance training: a meta-analysis. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2017;117(11):2335-2354. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-017-3720-z. doi:10.1007/s00421-017-3720-z

22. Munn J, Herbert RD, Gandevia SC. Contralateral effects of unilateral resistance training: a meta-analysis. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96(5):1861-1866. Available from: https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/japplphysiol.00541.2003?rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed&url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org. doi: /10.1152/japplphysiol.00541.2003

23. Barbalho-Moulim MC, Paro FM, Pedrosa DF, Serafim LM, Kuster E, Carmo WAD, et al. Effects of upper limbs’ neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) superimposed to voluntary contraction added to a protocol of intradialytic leg cycle ergometer exercise, in muscle strength, functional capacity and quality of life of adult patients with CKD: a randomized clinical trial protocol. Physiother Res Int. 2024;29(2):e2079. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pri.2079. doi:10.1002/pri.2079

24. Borg E, Kaijser L. A comparison between three rating scales for perceived exertion and two different work tests. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16(1):57-69. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00448.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00448.x

25. Parker K. Intradialytic Exercise is Medicine for Hemodialysis Patients. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2016;15(4):269-275. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/acsm-csmr/fulltext/2016/07000/intradialytic_exercise_is_medicine_for.12.aspx. doi:10.1249/JSR.0000000000000280

26. Green LA, Gabriel DA. The effect of unilateral training on contralateral limb strength in young, older, and patient populations: a meta-analysis of cross education. Phys Ther Rev. 2018;23(4-5):238–249. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10833196.2018.1499272. Doi:10.1080/10833196.2018.1499272

27. Barroso WKS, Rodrigues CIS, Bortolotto LA, Mota-Gomes MA, Brandão AA, Feitosa ADDM, et al. Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão Arterial – 2020. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2021;116(3):516–658. Available from: https://abccardiol.org/article/diretrizes-brasileiras-de-hipertensao-arterial-2020/. doi: 10.36660/abc.20201238

28. Bezerra P, Zhou S, Crowley Z, Brooks L, Hooper A. Effects of unilateral electromyostimulation superimposed on voluntary training on strength and cross-sectional area. Muscle Nerve. 2009;40(3):430-437. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mus.21329. doi: 10.1002/mus.21329

29. Duarte PS, Miyazaki MCOS, Ciconelli RM, Sesso R. Tradução e adaptação cultural do instrumento de avaliação de qualidade de vida para pacientes renais crônicos (KDQOL-SF TM). Rev Assoc Médica Bras. 2003;49(4):375–381. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/ramb/a/JxHTKxTw3WmQqNDPg3VLzgB/. doi:10.1590/S0104-42302003000400027

30. Hasan LM, Shaheen DAH, El Kannishy GAH, Sayed-Ahmed NA, Abd El Wahab AM. Is health-related quality of life associated with adequacy of hemodialysis in chronic kidney disease patients? BMC Nephrol 2021;22(1):334. Available from: https://bmcnephrol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12882-021-02539-z doi:10.1186/s12882-021-02539-z.

31. Pretto CR, Winkelmann ER, Hildebrandt LM, Barbosa DA, Colet CDF, Stumm. Quality of life of chronic kidney patients on hemodialysis and related factors. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2020;28:e3327. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/rlae/a/9JDNyTBwTMqt4br7svXJT4v/?lang=en . doi:10.1590/1518-8345.3641.3327

32. Mapes DL, Bragg-Gresham JL, Bommer J, Fukuhara S, McKevitt P, Wikström B, et al. Health-related quality of life in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(5 Suppl 2):54-60. Available from: https://www.ajkd.org/article/S0272-6386(04)01106-0/fulltext. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.08.012

33. Salhab N, Karavetian M, Kooman J, Fiaccadori E, El Khoury CF. Effects of intradialytic aerobic exercise on hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nephrol. 2019;32(4):549-566. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40620-018-00565-z. doi:10.1007/s40620-018-00565-z

34. Villanego F, Naranjo J, Vigara LA, Cazorla JM, Montero ME, García T, et al. Impact of physical exercise in patients with chronic kidney disease: Sistematic review and meta-analysis. Nefrologia. 2020;40(3): 237-252. Available from: https://www.revistanefrologia.com/es-linkresolver-impacto-del-ejercicio-fisico-pacientes-S0211699520300266. doi:10.1016/j.nefro.2020.01.002.

35. Segura-Ortí E, Martínez-Olmos FJ. Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change scores for sit-to-stand-to-sit tests, the six-minute walk test, the one-leg heel-rise test, and handgrip strength in people undergoing hemodialysis. Phys Ther. 2011;91(8):1244-1252. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/91/8/1244/2735175?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false. doi:10.2522/ptj.20100141

36. Heiwe S, Jacobson SH. Exercise Training in Adults With CKD: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(3):383–393. Available from: https://www.ajkd.org/article/S0272-6386(14)00735-5/abstract. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.03.020

37. Moura A, Madureira J, Alija P, Fernandes JC, Oliveira JG, Lopez M, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life perceived by end-stage renal disease patients under online hemodiafiltration. Qual Life Res. 2015; 24: 1327–1335. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11136-014-0854-x. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0854-x

38. Kim S, Nigatu Y, Araya T, Assefa Z, Dereje N. Health related quality of life (HRQOL) of patients with End Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD) on hemodialysis in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22: 280. Available from: https://bmcnephrol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12882-021-02494-9. doi:10.1186/s12882-021-02494-9

39. Thompson S, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Molzahn AA. A Qualitative Study to Explore Patient and Staff Perceptions of Intradialytic Exercise. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(6):1024–1033. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/cjasn/abstract/2016/06000/a_qualitative_study_to_explore_patient_and_staff.14.aspx. doi:10.2215/CJN.11981115